The sharp crack of the break elicits the echo of three knocks on the door. Jinnah opens the door to three well-dressed young Indian men. Law students, fresh from class at college, by the look of their ragged satchels. Decades ago, Jinnah looked much the same, allowing for changes in fashion. None of them have been here long, clearly. It is early October, and two of them are already wearing woollen mufflers against the cold.

‘Mr Jinnah!’ says one of them. ‘Sir, we are honoured to meet you.’

‘What is your business here?’

‘We wish to know what you thought of the pamphlet.’

‘I receive a half-dozen such things every week.’

The students look equally shocked and crestfallen. ‘The one about Pakistan! By Mr Choudhry Rahmat Ali!’

Jinnah raises an eyebrow. ‘About what?’

‘Pakistan.’

A made-up word, Pakistan—only fitting, for a made-up place. In English, the fairy-tale nature of the idea would come through better: Pureland, where all the boys are true believers, and all the girls are virgins until marriage. Pureland, where stones are never painted and garlanded, and boys and girls never, ever engage in nine nights of dance around a tiger-straddling Goddess. Only Purelanders live in Pureland, where the water is pure, and the daughters are pure, and the demographics are pure. Religion: Islam. Nationality: Pakistan.

‘I am not familiar with this,’ says Jinnah icily.

‘A homeland for the Muslims!’ shouts one of the students. ‘Hindustan for Hindus, Pakistan for Muslims. Anything less, and we will be overrun.’

Another student, crushing forward: ‘P for Punjab, A for Afghan, K for Kashmir, S for Sind!’

‘Baluchistan would be in there, too,’ adds the third student. ‘We’ll work a B into the name later.’

The students are pushing each other forward, crowding through the door—to the point that one of them brushes Jinnah’s seersucker suit coat. He looks down at the invisible stain and then back up at his visitors. They sense immediately that they have transgressed, and they shuffle back to stand at attention on his porch.

‘How long have you boys been involved in Indian politics?’

The students glance at each other. One speaks up, but sheepishly, with none of the fanatical glee of a moment before. ‘Since we got here, Mr Jinnah.’

‘How about in India, growing up?’

‘We were busy with our studies, sir.’

‘I assume from our conversation that it was an English medium school.’

‘Yes, it was, sir. St. Xavier’s, sir.’

‘Did you have Hindu boys in your class? Parsis? Christians?’

They nod.

‘And you all sat side by side and did your work?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘When it comes to school, then, it does not bother you that men of different classes and faiths sit peacefully and do their work. But when it comes to a society, to a nation, you need Muslims in front, in back, and at both elbows to feel at home?’

The students say nothing. Jinnah seems to have grown several feet in stature, dwarfing them.

‘The only good thing that has come out of the British Raj is the fact that no Indian can stand the British. And that unity of disgust is the only thing that will allow us to kick them out. Once they are out, we will be one of the largest nations on earth.’

A student digs in his satchel. ‘If you would only read the pamphlet—’

‘When you were in India, you never looked up from your textbooks, and now that you’re here, you don’t look up from your pamphlets. It may be pleasant to conjure up these fantastical wonderlands on a green lawn in London, but your elders at these Round Table talks are concerned with India as it is. Go study your books. Leave politics to us.’

The students are standing with their hands at their sides, their hats askew on their coconut-oiled heads. The weather gets colder where he gazes, and he is gazing right at them. Jinnah slams the door just as Fatima comes down the stairs.

‘Salesmen again?’

‘Of a kind.’

‘What were they selling?’

‘What all salesmen sell,’ he mutters. ‘A fantasy of ownership.’

Fati shakes her head. The year is 1931, and they are still new to Hampstead Heath. ‘I think I will answer the door from now on.’

‘And you will be sweet, Fati?’

‘Not at all. But at least I will help you spare your words for opponents that matter.’

Jinnah gathers the snooker balls into the triangle, but Fati does not bother to play against him: no matter who breaks, the game will end with Jinnah clearing the table by himself. Alone again: that is what he does. Beware a diaspora, Jinnah thinks to himself. Take a step back from a painting, and you can grasp the composition: put time between yourself and your great love, and you can see it for the infatuation it always was. Remove yourself from a place, though, and the opposite happens: it becomes a mere shape on a map, a word in a pamphlet, an idea in the heads of hotblooded young men. What a foolish idea, this Pakistan! As if water and ink could be corralled, by fiat, in two halves of the same glass! What of the granularity of villages, customs, tongues, sects, trades? Who was this Choudhry fellow, anyway? Had he done the hard, unrewarding work of politics, as Jinnah had? It was easy to scribble fever dreams in another country. Herzl had projected Zion from his study in Austria-Hungary. Ensconced in a London library, learning everything from newspapers, pamphlets and hearsay, could such immature young students even see their birthplace any more? That India of many minglings made; that quarrelsome India … ‘Pakistan’ was an abstraction, not a place where people lived. Divide it once, what was to keep it from dividing over and over? Ninety-nine squabbling Balkans—while the British tsk-tsked how much better off we were under the Raj … Jinnah shakes his head, thinking, No, not possible, but partly out of pity, too. Political deadlock has got to the point that people are turning to hopeless, unrealistic ideas like this one. Click. The white ball shivers back towards him, tracing a crescent on the green felt.

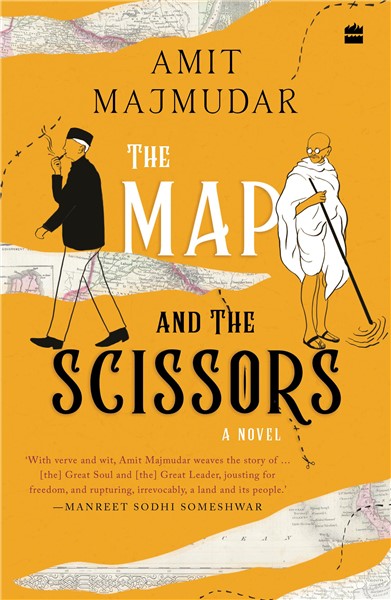

Published with permission from HarperCollins.

Read reviews of the book here.

Comments

This seems to be an interesting book provided it reveals something about partition that's not known so far.